GOTO Reconsidered

- Published on

Before I learned to program, I had used computers to play games like Solitaire and Road Rash and explore Microsoft Encarta. I had also taken a few computer classes in school, learning what parts computers had, who the pioneers of computing were, and how to navigate around Windows. But I hardly knew how computer applications worked, and I hadn't ever built one myself.

One day, my father brought home a CD collection of compilers, interpreters, and manuals for BASIC (QBasic and TBasic), Fortran, COBOL, and Pascal. And, like many other programmers, I wrote my first program to print out a message to the world:

PRINT "Hello World"As I worked through the QBasic manual, I learned about programming concepts like comments, variables, user input, math expressions, and conditional statements. One section of the manual covered the GOTO statement, a programming construct that is much less popular today but is worth giving another look.

What is GOTO?

The GOTO statement jumps from the current line in a program to another line. It performs a one-way transfer of control (which is to say, it does not return control to the current line, as a function call does). GOTO label jumps to the line with the given label. And, in BASIC, we can label lines with line numbers. For example, this program prints out successive positive integers:

10 LET X = 1

20 PRINT X

30 LET X = X + 1

40 GOTO 20We can also combine the GOTO statement with a conditional statement to perform a conditional transfer of control: IF condition THEN GOTO label. In this example, we only print out the first 20 positive integers:

10 LET X = 1

20 PRINT X

30 LET X = X + 1

40 IF X < 21 THEN GOTO 20In languages like C, we label lines with alphanumeric labels instead of line numbers. For example, this C program also prints out the first 20 counting numbers:

void main()

{

int x = 1;

next:

printf("%d\n", x);

x++;

if (x < 21) goto next;

}Assembly code

GOTOs compile into jump assembly instructions. This C program that prints successive positive integers...

void main()

{

int x = 1;

next:

printf("%d\n", x);

x++;

goto next;

}...compiles into this assembly code:[1]

; "local label" which stores the string constant we'll use to print later

.LC0:

.string "%d\n"

; label for the start of the main function

main:

; prepare the stack and registers for use

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 16

; move 1 into 4 bytes starting at the address rbp-4

; rbp-4 represents the variable x

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

; label for "next"

.L2:

; print the 4 bytes stored in rbp-4 using the string constant in .LC0

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-4]

mov esi, eax

mov edi, OFFSET FLAT:.LC0

mov eax, 0

call printf

; add 1 to the 4 bytes stored at the address rbp-4

add DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

; jump back to .L2

jmp .L2We call the statement in the last line an unconditional jump instruction. It tells the machine to jump to the section of code marked .L2.

Loops

You may have noticed that, in the examples we've seen so far, we use GOTOs to repeat a process, like a pseudo for or while loop. Indeed, we can rewrite the previous example with a while loop.

void main()

{

int x = 1;

while (1) {

printf("%d\n", x);

x++;

}

}This program doesn't just print the same output as the GOTO version, it has the exact same assembly code.

.LC0:

.string "%d"

main:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 16

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

.L2:

mov eax, DWORD PTR [rbp-4]

mov esi, eax

mov edi, OFFSET FLAT:.LC0

mov eax, 0

call printf

add DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

jmp .L2Conditional jumps

In the previous section, we also saw an example of a conditional GOTO: a GOTO combined with an if statement.

void main()

{

int x = 1;

next:

printf("%d", x);

x++;

if (x < 21) goto next;

}Here's the assembly code version of this new program:

.LC0:

.string "%d"

main:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

sub rsp, 16

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

.L2:

; ** we'll skip the printing and adding instructions... **

; compare 20 and the 4 bytes stored in rbp-4

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 20

; ...and, if the result is "greater than" (i.e. the 4 bytes in rbp-4 equal 21 or more), jump to .L3

jg .L3

; jump to .L2

jmp .L2

.L3:

; exit the program

nop

leave

retWe see a new type of jump instruction here, jg. jg jumps to a label if the result of the last arithmetic operation was "greater than".

je <label> (jump when equal), jne <label> (jump when not equal), and jl <label> (jump when less than) are some other examples of conditional jump instructions. These instructions correspond to combining GOTOs with if (a == b), if (a != b), if (a < b), respectively, etc.

We can rewrite this conditional GOTO program with a for loop instead. And again, this program prints the same output as its GOTO version using similar conditional jump statements.

void main()

{

for (int i = 1; i < 21; i++) {

printf("%d", i);

}

}Conditional blocks

Compilers also use conditional jump instructions for conditional blocks. Here's a program with an if-else structure outside a loop:

int main() {

int a = 0;

if (a == 1) {

a++;

} else {

a--;

}

}And its assembly instructions:

main:

push rbp

mov rbp, rsp

mov DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 0

cmp DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

jne .L2

add DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

jmp .L3

.L2:

sub DWORD PTR [rbp-4], 1

.L3:

mov eax, 0

pop rbp

retThe highlighted section, .L2, is the else block. We jump to the block from line 6 if the value of rbp-4 is not equal to 1. Line 7 represents the if block, and on the next line, we jump over the else section to the end of the program. In some sense, if-elses are GOTOs too.

Use

GOTOs were fairly common in high-level programs in the early days of programming. But, with time, it became clear that, when used carelessly, they create spaghetti code that is difficult to understand and unmaintainable.

In the 1960s and 1970s, structured programming techniques that focused on producing clear, quality programs became popular. These techniques favoured structured constructs, like blocks, loops, conditionals, and subroutines (functions) over GOTOs.

In 1968, Edsger Dijkstra wrote a critical letter about GOTOs where he argued that GOTO statements make it harder to analyze a program and verify its correctness. He concludes that they are "too much an invitation to make a mess of one's program," and should be abolished from all higher-level programs.

The structured program theorem, first published in 1966, also showed that sequences (execute one, then another), conditionals (execute based on a condition), and repetition (execute multiple times) are sufficient to represent any computer program. In other words, it is always possible to rewrite a program without GOTOs.

There's a good chance this isn't news to you. If you write modern high-level languages, you may have never needed to write a GOTO statement before. However, there are some situations where GOTO can be a good way, if not the optimal way, to solve a task.

Error handling

In Donald Knuth's 1974 paper, "Structured Programming with go to Statements," he found that GOTOs are a good way to solve some tasks in ALGOL programs.[2] One of the tasks was the error exit.

Sometimes, when an error happens in a program, we skip over the rest of the code to perform some cleanup tasks, like deallocating resources and closing connections, instead. In languages like JavaScript, we can handle errors with exceptions and try-catch blocks:

function main() {

let db;

try {

db = connectToDB();

const result = db.query();

} catch (err) {

if (db) db.close();

}

}When Knuth wrote his paper in 1974, the most common programming languages did not support such structured exception handling. And neither does C, which is still widely used today. In the absence of exceptions and try-catch blocks, we can use GOTOs to handle errors:

void main()

{

struct *db;

struct *migrate_res;

struct *update_res;

db = get_db();

if (db == NULL) {

fprintf("could not get db\n");

goto err;

}

migrate_res = migrate_db(&db);

if (res == NULL) {

fprintf("could not migrate the db");

goto err;

}

update_res = update_data(&db);

if (update_res == NULL) {

fprintf("could not update data");

goto undo_migration;

}

// everything went fine, return

return 0;

undo_migration:

undo_migration(&db);

err:

return -1;

}Multi-level breaks

In languages like JavaScript, you can break out of a nested loop using a labelled break statement.

function main() {

loop1: for (let i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

loop2: for (let j = 0; j < 5; j++) {

if (i * j > 10) {

break loop1;

}

console.log(`i = ${i}, j = ${j}`);

}

}

console.log('finished printing counters with product <= 10');

}But in languages, like C, which do not have labelled breaks (and labelled continues), GOTOs can act as substitutes.

void main()

{

for (int i = 0; i < 5; i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < 5; j++) {

if (i * j > 10) {

goto done;

}

printf("i = %d, j = %d\n", i, j);

}

}

done:

printf("finished printing counters with product <= 10");

}There are a few alternative solutions to this problem. We could wrap the loops in another function and return from the function when we meet the condition; or, we could add a boolean flag. But it isn't clear that these alternatives would make the program any clearer or easier to understand.

Because the program with the GOTO statement is functionally the same as the one with the labelled break, you may also suspect that breaks and continues, whether labelled or unlabelled, are only fancy jump assembly instructions too. And you would be correct.

Finite state machines

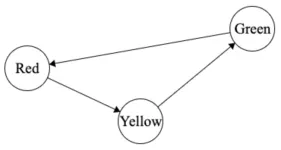

GOTOs can also represent finite state machines. A finite state machine is a model of a machine with a fixed number of states. The machine can only be in one state at a time and can transition from one state to the other based on some input.

For example, a traffic light is a finite state machine with three states: red, yellow, and green. Based on a timer, the indicator changes from red to yellow to green and back to red again.[3]

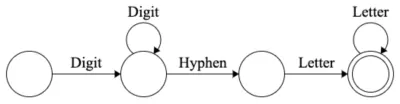

Regular expression matchers are also finite state machines. For example, ^[0-9]+\-[a-z]+$ matches a sequence of one or more digits followed by a hyphen followed by one or more letters.

We can write a function in C that matches this regex expression using GOTOs:

int matches(const char* str)

{

const char* curr = str;

// Fail if the string is empty

if (!curr) return 0;

firstDigit:

// Fail if the next character is not a digit

if (!isDigit(*(curr++))) return 0;

nextDigits:

// Skip over any more digits

if (isDigit(*(curr++))) goto nextDigits;

hyphen:

// We've moved one character past the non-digit, so move back one step

curr--;

// Fail if the next character is not a hyphen

if ((*(curr++)) != '-') return 0;

firstLetter:

// Fail if the next character is not a letter

if (!isLetter(*(curr++))) return 0;

nextLetters:

// Skip over any more letters

if (isLetter(*(curr++))) goto nextLetters;

// We've moved one character past the non-letter, so move back one step

curr--;

// Fail if there are any other characters after the last letter

if(*curr) return 0;

// All is well, return true

return 1;

}Again, there are other ways to write this matcher. We could use loops and breaks or a generic regex library[4] in place of the GOTO statements. But if we don't have such a library or we don't want to use one, GOTOs can be a simple, clear way to represent the states and transitions of a finite-state machine.

Support

JavaScript and Java both don't support GOTO, but they have labelled continues and breaks to repeat or exit nested loops. Java once had GOTO, but it was removed in its early days.

Python also doesn't have GOTO, but some libraries mimic the functionality. One library uses trace to change the program execution, and another works by rewriting the compiled bytecode. One Ruby library also adds GOTO to the language by rescuing raised exceptions and replaying the stack. These libraries are all experimental. Use them with caution.

Many other high-level programming languages have GOTO statements along with different safety controls.

In C, the GOTO statement is local to a function: the statement must be in the same function as the label it is referring to.[5] And the jump can't enter the scope of a variable-length array or another variably-modified type.[6] In C++, the jump also can't enter the scope of any automatic variables.[7]

In Go, GOTO can also only jump to a statement within the same function, and it must not cause any variable to come into scope that was not in scope at the point of the GOTO.[8] Similarly, in PHP, a GOTO statement can't jump into a function or method or out of one. The target label must be within the same file and context.[9] In both Go and PHP, GOTO can't jump into a loop or switch structure but can jump out of them to exit deeply nested loops.

GOTO in C# is also function-scoped, although it can jump from one case statement to another within a switch structure.[10] In these languages, GOTO statements can still produce clear, readable, and maintainable programs when used thoughtfully.

Compiled with x86-64 GCC 10.2 https://godbolt.org/ ↩︎

Donald E. Knuth. 1974. Structured Programming with go to Statements. ACM Comput. Surv. 6, 4 (Dec. 1974), 261–301. DOI:https://doi.org/10.1145/356635.356640 ↩︎

Unless you're in a left-lane country, where it changes from green to yellow to red and back to green again. ↩︎

Interestingly, some regex libraries like re2 work by generating finite-state machines like ours. ↩︎

C also provides

setjmpandlngjmp, however. When combined, these functions can perform non-local jumps across multiple levels of function calls. GOTO on steroids. ↩︎https://www.php.net/manual/en/control-structures.goto.php ↩︎

https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/dotnet/csharp/language-reference/keywords/goto ↩︎