Stacks on a Grid

- Published on

Sometimes when I'm trying to understand a programming problem or an algorithm, I try to build a mental picture of what the program is doing: How does one thing lead to another? How are the data structures changing over time? At what point does something get called or discarded?

So far, one of my learning interests has been to explore better ways to visualize that mental picture to better understand how programs work. In my previous writing on tries and quadtrees, I tried to show, along with the descriptions and source code of the data structures, exactly how it looks to add to or search through a trie or quadtree.

I recently got to make a toy language to explore that interest a little further. Last weekend, I joined a coding jam called Lang Jam; it's like a game jam, where participants try to make a video game from scratch in around one to three days of coding, but for making a programming language. I've recently been learning about languages, and a language-focused jam seemed like a great way to hack on something new.

The theme for the jam was "Beautiful Assembly", and the prompt was:

"Assembly can mean a number of different things. For example, it could mean the most fundamental language a human can write to interact with a computer, the act of building something, or what has been built. Let your imagination run wild."

At first, I was a little worried about the theme because I had little experience working on low-level assembly programming. And after thinking for a while, my only broad idea was a language with an assembly-like syntax and a visual element that leaned into the "beautiful" part of the theme.

For inspiration, I browsed through the Esolangs wiki, a wiki page for languages that are "unique, difficult to program in, or just plain weird", and my goal was to find languages with assembly-like syntaxes and low-level constructs. I found languages like Super Stack!, which has one program stack and a handful of instructions that can manipulate the stack, and Kipple, which has 27 stacks and a single control structure.

The other source of inspiration for the language I planned to make was my existing interest in grids and spreadsheets. My first post on expression evaluators, where I first started learning about programming languages, came from my curiosity about how expression evaluation works in spreadsheet cells. I also once played around with using spreadsheets to solve Advent of Code questions.

Altogether, my idea was to make a language where you use an assembly-like syntax to interact with a grid of cells, much like you use formulas to compute cells in a spreadsheet. Inspired by the two languages from the wiki, I made the language stack-based and eventually named it StackGrid.

The core idea of StackGrid is that the input format (as well as the interpreter's state) is a grid of cells containing instructions and data. The instructions have an assembly-like syntax, with the instruction name followed by zero or more operands.

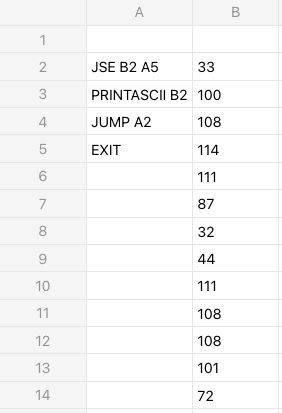

Here's how you might write a "Hello World!" program in StackGrid:

The numbers in column B are "Hello World!" in ASCII, bottom-up. The interpreter starts at cell A1 and continues down the A column until it reaches an EXIT instruction. The command in cell A2 jumps to cell A5 (which exits the program) if the stack[1] starting from cell B2 (that is, the value of the last non-empty cell reading from B2 downwards) is empty. A3 prints the top of the B2 stack as an ASCII value. (In the first run, this will be 72, or "H".) Finally, A4 jumps back to cell A2 to continue the print loop.

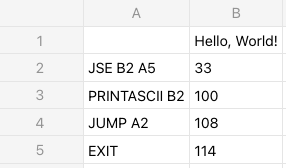

StackGrid has no explicit comment syntax. The interpreter ignores any cell that isn't in the instruction path or used as data by an instruction. Here's the same "Hello World!" program, but with a title comment in cell B1:

Besides JSE (jump when a stack is empty), JUMP (unconditional jump), PRINTASCII (print cell value as ASCII), and EXIT, StackGrid also features instructions like JEQ/JNE (jump when the top values of two stacks are equal/not equal), READASCII (read from stdin into a stack as ASCII), INC (increment value at the top of a stack), COPY (copy a stack into another stack), and more.

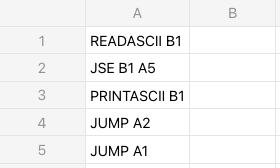

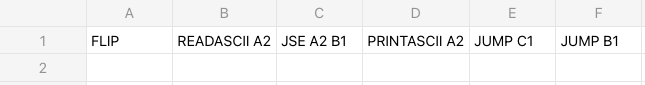

One particularly interesting instruction is FLIP. When called, the interpreter changes the direction of the instruction pointer from vertical to horizontal and vice-versa. By default, the interpreter reads downwards along the A column. But after calling FLIP, it will begin to read from left to right across the current row. As an example, these two programs both implement a simple cat (read from stdin into a stack, print the stack to stdout, read again):

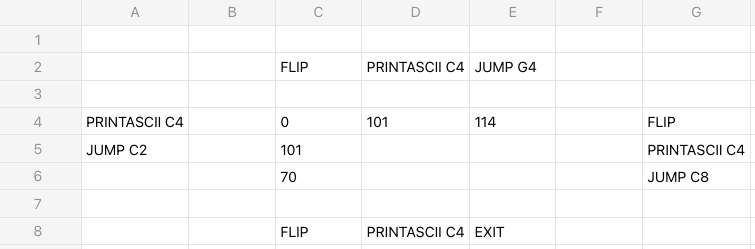

With these instructions, I tried to imagine what programs might look like if you could write out commands in different layouts in 2D. Here's a StackGrid program that prints "Free":

At cell A4, the program prints "F", then jumps to C2 and prints "r", then jumps to G4 and prints "e", then to C8 and prints the second "e". Notice how the commands are first vertical, then horizontal, then vertical again, then horizontal again, with the ASCII codes for "F", "r", "e", and "e" enclosed by a rectangle of commands. Go To statement in 2D considered very harmful.

I also wanted to explore making the interpreter interactive, or at least visualizable. Can we see what the interpreter is doing? For this, I made an online playground that runs StackGrid programs and added a "Replay" feature that can replay the interpreter's state.

Here's FizzBuzz on the playground. After running the program and hitting "Replay", watch the interpreter increment the loop counter at E2, compare it to 15 (at C14), 3 (at C2), and 5 (at C8), and copy the ASCII values of "Fizz", "Buzz", and "FizzBuzz" to F4 for printing:

While I only got to work on StackGrid for a brief period and don't plan to work on it much further, there are a few improvements I would have liked to make if I did.

First, jump instructions target cells by their addresses, like JUMP E9, which fits well with StackGrid's syntax, but isn't pleasant to use. If a command moves to a different cell—for example, if you add another command before it—all jump instructions pointing to it need to be updated. Is there a way to implement jumping to a label instead of a cell address that still fits in well with the StackGrid syntax?

Also, is it possible to make a numerical representation of instructions such that one instruction can meaningfully read another as data? Finally, the playground can be more interactive. Can a user pause the interpreter in the middle of execution, view the current location of the instruction pointer, modify the grid, and continue from an arbitrary cell, much like a typical debugger?

While I won't be using StackGrid to build real applications anytime soon, I think it made for a weird, fun language to create.

Check out the source code for the StackGrid interpreter and the web playground.

Stacks in StackGrid aren't quite stacks in the conventional sense. Since a stack can start from any arbitrary cell, instructions always start from the bottom of the stack and then walk up to find all the non-empty cells. So, operations like pushing, peeking, and popping a stack are all O(n) instead of the typical O(1). ↩︎