The Tradeoffs We Make

Building software is as much about making tradeoffs as it is about writing code. It involves making decisions about what tools and techniques to use. In a tradeoff, choosing some benefit from an alternative comes at a cost. There are no right or wrong answers, only better or worse choices in the context of the requirements and available resources.

Space-time

One common tradeoff in software engineering is the space-time tradeoff. In some processes, it is possible to reduce computation time by using more memory or disk storage. For example, here's a program that prints out the intersection between two arrays, m and n:

// Prints all elements that exist in both m and n

function intersection(m, n) {

// For each element in m...

for (i = 0; i < m.length; i++) {

// Check each element in n

for (j = 0; j < n.length; j++) {

// If the element exists in both m and n, print the element

if (m[i] === n[j]) console.log(m[i]);

}

}

}

// intersection([1, 5, 2, 9], [5, 4, 9, 0])

// > 5

// > 9

This program has a space complexity of O(1) and a time complexity of O(m*n). But we can improve the time complexity by using some more memory:

function intersection(m, n) {

const s = {};

// Store all elements in m in a map

for (i = 0; i < m.length; i++) {

s[m[i]] = true;

}

// For each element in n

for (i = 0; i < n.length; i++) {

// If the element exists in the map, print the element

if (s[n[i]]) console.log(n[i]);

}

}

This version has a space complexity of O(m) and a time complexity of O(m+n). By storing the first array's elements in a map, we reduce the time complexity of the program from quadratic time to linear time.

We trade space for time in other ways. For example, we sometimes use caching to store frequently requested data instead of re-querying a database. We can serve client requests quicker at the cost of the memory overhead introduced by the caches.

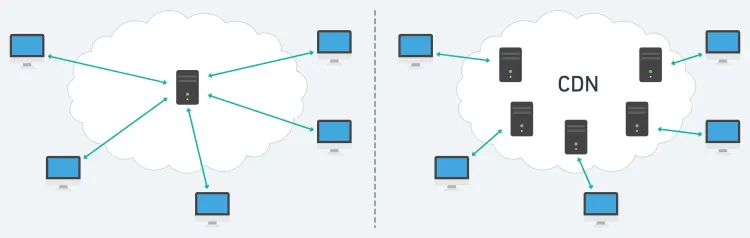

Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) also work as caches. They serve HTML documents, stylesheets, scripts, and media files from a globally distributed network of servers. Instead of sending requests to a single global server, clients send requests to the network. The CDN reduces the time it takes to retrieve a resource at the cost of more storage space.

Distributed databases

We also make tradeoffs in distributed databases. Say we have a database that stores application data and responds to user queries. We can replicate the database into secondary nodes and distribute incoming read traffic across the nodes.

After the primary node receives a write request, it needs to inform the other nodes about the updates. But it takes some time to send those updates. If a client tries to read from a secondary node before the time difference elapses, the client may get stale data.

We have two choices here. On receiving a write request, the primary node can update its copy of the data and then inform the client that the write was successful. Then, it would replicate the updates to the other nodes asynchronously. In this case, we say that the database does not have linearizability. After a successful write request, a secondary node might still return a stale read for some time.

Alternatively, the primary node can wait for all the nodes to update their copies of the data before confirming that the write is successful. This configuration would be linearizable. Every read request would return the most up-to-date view of the data from the last successful write request. But the cost would be that write requests take longer to complete.

In these two examples, we assume that the database nodes can communicate with one another. But what happens if they can't? In the event of a network partition, a disconnected node can't guarantee that its data is up to date.

Again, we have two options. The secondary node can respond with an error. Instead of returning possibly-stale data, the node chooses to be unavailable. Or, the node can favour availability over linearizability and return its current data.

In the event of a partition, the latency-linearizability tradeoff becomes an availability-linearizability tradeoff. Together, these two tradeoffs are formally known as the PACELC theorem. PACELC is an extension of the CAP theorem, which only considers the latter tradeoff.1

Being thoughtful

Building useful software requires being thoughtful about making good tradeoffs. It takes a deep understanding of requirements, constraints, resources, and the pros and cons of the alternatives.

While making these decisions, we should ask: What do users expect from this software? Strong consistency could be critical for a financial application. But, for a blog? Probably not. We should also find out how to use available resources to get the results we want. The space-time tradeoffs we discussed earlier were reasonable because memory was accessible.

Using precise language clears the path towards making better decisions. Instead of saying an alternative is "faster" or "more reliable", use more specific terms. Be less vague. "Faster" by how much? By how many seconds? Or by what percentage? "More reliable" under what conditions?

Vague descriptions can hide the full scope and impact of choosing certain alternatives. An option might perform abysmally under certain important conditions, even though it performs well on average. According to some ancient folklore, knowing the true name of a being gave you complete control over it. The mytheme rings true here. As we ask more probing questions to uncover the full impact of a tradeoff—its true name—we gain more control over the overall decision.

Learning to make thoughtful tradeoffs is also a key part of becoming a technical leader. Good engineering leadership involves understanding the context behind engineering decisions and re-evaluating the decisions when requirements change. As the memes go: becoming a senior engineer is saying "it depends" over and over again until you retire.

In any case, making good tradeoffs is a skill every software engineer should learn. These decisions make significant differences. And thinking about them carefully helps ensure that we build software that remains valuable to users.

Footnotes

-

In practice, these tradeoffs aren't so binary. A system that is not CAP-available may still be available to process requests from other nodes. And a system that is not CAP-consistent (or linearizable) can still offer weaker forms of consistency, like sequential and causal consistency. There are many possible permutations of availability and consistency levels. But the tradeoffs themselves don't disappear. Whichever way we turn, decisions we make about the consistency of distributed networks affect latency and availability and vice-versa. ↩