Redraw Only The Diff

- Published on

To illustrate the concepts in some of the posts on this blog, I sometimes make small, interactive JavaScript programs (see Conway's Game of Life, Quadtrees in the Wild, and Building Ayòayò: Web Application, for example).

Most of these programs are in plain JavaScript (to move HTML elements around or draw on a canvas element). Others use libraries like D3.js. But the general idea is usually the same: when someone clicks or presses a key, draw something on the page.

While making these interactive programs, I've learned a simple but useful UI optimization: when rendering from state, redraw only the changed views.

Imperative and declarative rendering

Say we want to write a program that draws a 5px-wide circle when someone clicks on the page. Here's one way to do it:

const ctx = canvasElement.getContext('2d');

canvasElement.addEventListener('click', (evt) => {

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.arc(evt.clientX, evt.clientY, 5, 0, 2 * Math.PI);

ctx.stroke();

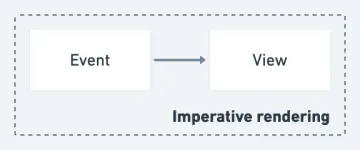

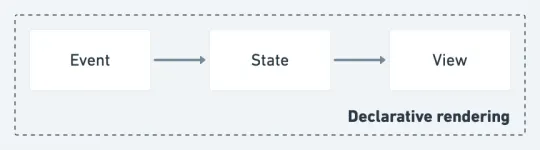

});We may call this an imperative approach to rendering. When we receive an event, we draw on the screen step-by-step.

Alternatively, we can take a declarative approach. We can model the view as a function of the current state of the system. Then, when we receive an event, we compute the next state of the system and redraw the view based on the new state.

A good example of this approach is the program from my most recent post on Conway's Game of Life.

The Game of Life runs on a 2-D grid of square cells. Each of the cells can either be live or dead. And at the next turn of the game, the state of each cell may change according to a set of rules: live cells with too many or too few live neighbours die; dead cells with just enough live neighbours become live.

We can implement the set of rules in a function called next. We don't need to care about what next actually does. What's important is knowing that it accepts the grid representing the current generation of the game and returns the grid representing the next generation.

next: (grid: Boolean[][]) => Boolean[][]We can then write a render function that draws a grid on the screen.

function render(grid) {

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

// For each cell in the grid...

for (let row = 0; row < grid.length; row++) {

for (let col = 0; col < grid[row].length; col++) {

const cell = grid[row][col];

// Draw the cell

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.fillStyle = grid[row][col] ? liveColor : deadColor;

// (x, y, width, height)

ctx.rect(col * cellWidth, row * cellWidth, cellWidth, cellWidth);

ctx.fill();

}

}

}By wrapping all the imperative code in one function , we can use a declarative API to draw the animation. We tell render what we want the grid to look like, and it handles the rest.

// Draws the next generation of the grid every `minInterval` milliseconds

function onNextAnimationFrame(timestamp) {

if (timestamp - lastTimestamp >= minInterval) {

grid = next(grid);

render(grid);

lastTimestamp = timestamp;

}

window.requestAnimationFrame(onNextAnimationFrame);

}

window.requestAnimationFrame(onNextAnimationFrame);The Game of Life program also lets users toggle the state of a cell by clicking on it. We can implement this declaratively as:

canvasElement.addEventListener('click', (evt) => {

// Find the position of the cell in the grid

const col = Math.floor(evt.clientX / cellWidth);

const row = Math.floor(evt.clientY / cellWidth);

// Get value of new grid with the cell toggled

const nextGrid = clone(grid);

nextGrid[row][col] = !nextGrid[row][col];

// Render the new grid

grid = nextGrid;

render(grid);

});Declarative rendering simplifies the implementation by introducing an abstraction layer between the event and the view. Instead of immediately drawing on the page when an event happens, we determine what the state should be and then render() the state.

We should expect the same view whether we render imperatively or declaratively. But are both approaches really the same?

The trouble with being declarative

Consider an imperative version of the previous example:

canvasElement.addEventListener('click', (evt) => {

// Find the position of the cell in the grid

const col = Math.floor(evt.clientX / cellWidth);

const row = Math.floor(evt.clientY / cellWidth);

// Toggle cell

grid[row][col] = !grid[row][col];

// Draw cell

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.fillStyle = grid[row][col] ? liveColor : deadColor;

ctx.rect(j * cellWidth, i * cellWidth, cellWidth, cellWidth);

ctx.fill();

});When we compare this to the declarative version, it becomes clear that the latter does a lot of unnecessary work. Even though only one cell changes, the render function redraws the entire grid.

To fix this, we can modify render to only redraw the changed cells (the "diff").

function render(grid) {

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

for (let i = 0; i < grid.length; i++) {

for (let j = 0; j < grid[i].length; j++) {

// Redraw the cell only if this is the first render or the cell has changed

if (!previousGrid || previousGrid[i][j] !== grid[i][j]) {

// draw...

}

}

}

previousGrid = grid;

}Now, when someone toggles one cell, only that cell will be redrawn. And when the game is running, only the cells that have changed since the previous generation will be redrawn.

With this "diffing-the-next-state" optimization, games with large grids perform much better.

But while the optimization worked well in this example, it can be limited in some other use cases. To see what these limitations are, we'll take a detour into the foremost declarative UI library in JavaScript-land: React.

When it's difficult to diff

Say we want to write a program that displays the number of times someone has clicked on a button. We can write this as:

// HTML:

// <p>I am a click counter!</p>

// <button>Click</button>

// <div>Clicked <span>0</span> times!</div>

const buttonElement = document.querySelector('button');

const countTargetElement = document.querySelector('span');

let count = 0;

buttonElement.addEventListener('click', () => {

countTargetlement.textContent = String(++count);

});As we've seen earlier, this is an imperative approach to rendering. On receiving a click event, we directly change the view.

Alternatively, React lets us write this program declaratively:

function ClickCounter() {

const [count, setCount] = useState(0);

return (

<>

<p>I am a click counter!</p>

<button onClick={() => setCount(count + 1)}>Click</button>

<div>

Clicked <span>{count}</span> times!

</div>

</p>

);

}We tell React how to translate the click event to a new state (() => setCount(count + 1)) and how to translate the state to a view (return <>...</>). And React handles everything else.

But we run into a similar issue as we did with the declarative implementation of the Game of Life. When we generate an updated view from the new state, we find that some parts of the view have not changed (in this case, for example, the <p> element). And just like we checked that the value of a cell had changed before redrawing, to remain performant, React checks to see which elements have changed since the previous state and only applies the diff to the DOM.

To diff efficiently, React keeps an internal representation of the DOM. This "virtual DOM" holds the React elements that represent the rendered UI. When state changes, a React component generates a new tree of React elements. React compares this new tree with the previous tree and only applies the diff to the real DOM.

But in some cases, it can be difficult to find the correct diff. For example, if we sort the list below alphabetically, React will mutate every child element instead of re-ordering them. This inefficiency can become significant in large lists.

// Before

<ul>

<li>first</li>

<li>second</li>

<li>third</li>

<li>fourth</li>

<li>fifth</li>

</ul>

// After

<ul>

<li>fifth</li>

<li>first</li>

<li>fourth</li>

<li>second</li>

<li>third</li>

</ul>For this reason, React provides a key attribute to match children in the original tree with children in the subsequent tree, which makes the tree conversion more efficient.

// Before

<ul>

<li key="first">first</li>

<li key="second">second</li>

<li key="third">third</li>

<li key="fourth">fourth</li>

<li key="fifth">fifth</li>

</ul>

// After

<ul>

<li key="fifth">fifth</li>

<li key="first">first</li>

<li key="fourth">fourth</li>

<li key="second">second</li>

<li key="third">third</li>

</ul>But in some other cases, even the key property isn't enough to help React efficiently find the diff. In the current implementation of React's reconciliation algorithm, you can express that an element has moved amongst its siblings. But you cannot tell React that it has moved somewhere else.

React will re-render <Target /> as it moves outside its parent.

const targetElement = <Target />;

// Toggles `targetElement` between two different parents

function TargetToggler() {

const [inDefaultPosition, setInDefaultPosition] = useState(true);

return (

<>

<button onClick={() => setInDefaultPosition(!inDefaultPosition)}>Toggle</button>

<div className="default-position">

{/* Element is here when `inDefaultPosition` is true */}

<p>{inDefaultPosition && targetElement}</p>

</div>

<div className="non-default-position">

{/* Element is here when `inDefaultPosition` is false */}

<p>{!inDefaultPosition && targetElement}</p>

</div>

</>

);

}Recap

Computing a diff before re-rendering is useful when it's easier to find the diff than to render. In the Game of Life program, comparing the current and next states of the cell takes less time than redrawing the cell. And in React, comparing two trees of React elements takes less time than rendering the entire tree on the real DOM. If it took more time to produce the diff than to render, it would be more reasonable to just redraw the entire view.

The diff optimization is also useful when most of the view remains the same between states. In the Game of Life program, only one cell in the grid changes when someone clicks the grid. And when the game is running, only the cells close to live cells change state. In the React components we saw, only a few properties of the tree (like the text content) changed between states, while most of the DOM remained unchanged. If most of the view changes between states (for example, in games with moving cameras), diffing only ends up introducing additional overhead.

With those considerations in mind, we can recap: when rendering a view declaratively from state, if only some of the view changes between states, and it takes much less time to compute a diff than to render, redraw only the diff.