Introductions, Math Games, and UI Optimizations

Once a month or so, since May 2020, I write an article about a programming topic on my blog. So far, I've written about the spam filter that inspired Bitcoin, how Go slices work, the GOTO statement, building the game of Ayoayo, and more.

I've enjoyed writing these articles, but I've also realized that some topics I want to write about don't fit neatly into the blog's essay format. Each blog post takes days—some even weeks—to research and write. But I also want to write more casually about programming.

That's what this newsletter is about. I'll share updates when I publish new articles on my blog. And I'll also write some commentary about the articles: notes, related content, additional reading material, and so on. Otherwise, I'll write about what I'm learning or building, plus any other relevant programming-related links I find.

If any of that sounds interesting to you, consider sharing this newsletter with others who might like it or subscribing if you haven't already done so. (If you are reading this as an email, it means you subscribed even before I wrote the first issue or publicly shared the newsletter. Thank you!)

The Game of Life

I published two new articles on my blog last week, and the first one was about John Conway's Game of Life.

If you're not familiar with the Game of Life, it's a game that runs on a 2D grid of square cells. Each cell can either be live or dead. And after each turn of the game, the cells transition based on a few simple rules:

- Live cells with fewer than two live neighbours die

- Live cells with two or three neighbours remain alive

- Live cells with more than three neighbours die

- Dead cells with exactly three live neighbours become alive

The kicker, though, is that these four simple rules give rise to very complex behaviour. You can create patterns that oscillate, patterns that move across the screen, patterns that can create copies of themselves, patterns that can simulate the Game of Life itself. It's a simple and fun program to write, but it's also a curious lesson about emergence: how the interactions of simple entities can create complexity.

I also built a demo of the game and shared the writing and building process on Twitter. If you want to learn more about the history of the game, there's a really good documentary about it on YouTube.

Redraw only the diff

The second article from last week is a bit of a meta-article. It's an article about how I write articles—or, more specifically, about an optimization I use when I build interactive programs for my articles.

When I build interactive programs, there are typically two ways to render on the UI: imperative or declarative rendering. The difference between the two approaches is that declarative rendering introduces a layer of abstraction (the state) between an event and what is rendered on the screen.

In the Game of Life program, for example, if we wanted to toggle a cell in the grid imperatively, we could write:

canvasElement.addEventListener('click', (evt) => {

// Find the position of the cell in the grid

const col = Math.floor(evt.clientX / cellWidth);

const row = Math.floor(evt.clientY / cellWidth);

// Toggle cell

grid[row][col] = !grid[row][col];

// Draw cell

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.fillStyle = grid[row][col] ? liveColor : deadColor;

ctx.rect(j * cellWidth, i * cellWidth, cellWidth, cellWidth);

ctx.fill();

});

But alternatively, with a declarative approach:

canvasElement.addEventListener('click', (evt) => {

// Find the position of the cell in the grid

const col = Math.floor(evt.clientX / cellWidth);

const row = Math.floor(evt.clientY / cellWidth);

// Get value of new grid with the cell toggled

const nextGrid = clone(grid);

nextGrid[row][col] = !nextGrid[row][col];

// Render the new grid

grid = nextGrid;

render(grid);

});

function render(grid) {

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

for (let row = 0; row < grid.length; row++) {

for (let col = 0; col < grid[row].length; col++) {

const cell = grid[row][col];

// Draw cell

ctx.beginPath();

ctx.fillStyle = grid[row][col] ? liveColor : deadColor;

ctx.rect(col * cellWidth, row * cellWidth, cellWidth, cellWidth);

ctx.fill();

}

}

}

Note the difference between the two approaches. The declarative version converts the action to a new game state first before rendering the updated state to the page.

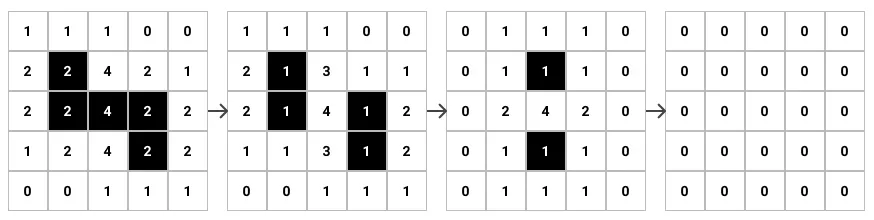

Both approaches produce the same view. But when we render declaratively, we redraw all the cells, including those that have not changed. Instead, we can redraw only the "diff" of the state, i.e. only redraw the cells that have changed:

function render(grid) {

const ctx = canvas.getContext('2d');

for (let i = 0; i < grid.length; i++) {

for (let j = 0; j < grid[i].length; j++) {

// Redraw the cell only if this is the first render or the cell has changed

if (!previousGrid || previousGrid[i][j] !== grid[i][j]) {

// draw...

}

}

}

previousGrid = grid;

}

This optimization significantly improves the performance of the Game of Life programs with large grids.

In the rest of the post, I discuss how React's reconciliation algorithm runs a similar optimization. I also share a few use cases where the optimization is limited.

Before you go

You may have noticed this newsletter doesn't exactly have a name; it just says "Chidi's Newsletter". If you have any name suggestions, or you think "Chidi's Newsletter" works fine, or you have any other general feedback, please let me know. It's as easy as responding to this email.

— Chidi